Behavioural activation: Re-engaging With Life When Living With Chronic Pain

Joon Choi, Clinical Psychologist

Persistent pain affects more than the body. It influences mood, motivation, daily routines, and how people participate in activities that matter to them (Nicholas, Costa & Hancock, 2023). Over time, many individuals notice that their world becomes smaller. They withdraw from social situations, physical tasks, and enjoyable activities. This pattern, although understandable, can inadvertently reinforce both pain and low mood (Lee et al., 2021).

Behavioural activation is a psychological strategy that helps people gradually re-engage with meaningful activity in a planned and sustainable way. Behavioural activation is an important psychological treatment strategy and is commonly included as part of a comprehensive pain management program. This blog outlines how behavioural activation works and why it can be an important tool for people living with persistent pain.

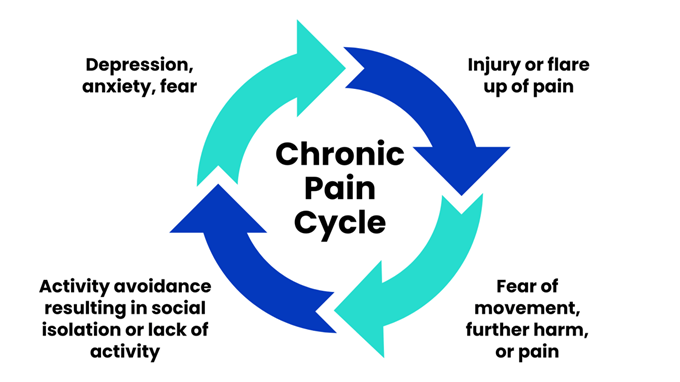

Understanding the pain–mood–activity cycle

Persistent pain often leads to reduced activity. This may begin with avoiding tasks that increase symptoms but can gradually extend to other areas of life. Reduced activity can lead to:

Lower mood

Increased fatigue

Reduced fitness and mobility

Decreased confidence

Greater focus on pain

These changes can make pain feel more intense and more limiting. The result is a cycle of pain, low mood, and avoidance that sustains itself over time. Behavioural activation aims to interrupt this cycle by using structured activity planning to rebuild confidence, mood, and function.

What is behavioural activation?

Behavioural activation is an evidence-based psychological approach originally developed for depression (Donaldson, Lamont & McMillan, 2022). It focuses on increasing engagement in activities that are meaningful, enjoyable, or create a sense of achievement. The principle is simple: mood improves when people participate in valued activities, and mood declines when activity levels drop.

In the context of persistent pain, behavioural activation helps individuals:

Understand avoidance patterns

Identify meaningful goals

Break tasks into manageable steps

Rebuild daily structure and routine

Improve mood and energy

Increase physical and social engagement

Gradually reduce disability

Importantly, behavioural activation does not require “pushing through pain”. Instead, it uses graded, consistent activity that matches an individual’s capacity and gradually expands over time.

Why avoidance increases pain over time

Avoidance is a natural response to discomfort. For short-term injuries, rest helps healing. For persistent pain, however, long periods of rest or inactivity can reduce conditioning and increase sensitivity in the nervous system (Ellingson et al., 2012). This can make even small tasks feel more painful.

People often describe two common patterns.

Boom-and-bust pattern

On a good day, they attempt to “catch up,” doing too much at once. This leads to a flare-up, followed by several days of reduced activity. Over time, this creates instability in mood and routine

Increasing avoidance

Activities once considered manageable are postponed or removed altogether. Although avoidance reduces discomfort temporarily, it reinforces the belief that pain signals danger, which can contribute to ongoing disability

Behavioural activation helps stabilise activity across the week and rebuild confidence safely.

How behavioural activation helps

Identifying what matters

Behavioural activation starts by identifying important life areas, such as family, work, leisure, health, or independence. Understanding what is meaningful provides direction for goal setting

Using micro-goals

Large tasks can feel overwhelming. Behavioural activation breaks them into small, achievable steps. Examples include:

Walking for two minutes

Doing one load of washing

Sitting outside for fresh air

Calling a friend

Preparing a simple meal

Success with small goals builds momentum and confidence

Increasing pleasant and mastery activities

Behavioural activation balances different types of activities

Pleasant activities (e.g. listening to music, reading, hobbies) support mood

Mastery activities (e.g. completing household tasks, work-related tasks) build confidence

Both are important for people with persistent pain

Rebuilding daily structure

A predictable routine helps regulate mood, sleep, and energy. Behavioural activation supports patients in creating a weekly schedule that includes self-care, rest, activity, and pacing

Supporting pacing and graded activity

Behavioural activation complements pacing principles by encouraging steady, consistent activity rather than fluctuating between overactivity and rest

Strengthening identity and quality of life

Over time, re-engaging with valued activities helps people reconnect with roles, relationships, and goals that may have been overshadowed by pain

Integrating behavioural activation within pain management

Within the pain management program, behavioural activation is often combined with:

Pain education

Physiotherapy and graded exercise

Psychological strategies for managing worry or low mood

Pacing and activity planning

Goal setting

Support around return-to-work

This multidisciplinary structure helps people understand their pain, improve daily functioning, and gradually re-engage with meaningful aspects of life (Kamper et al., 2015).

Summary

Behavioural activation is a practical and effective strategy for people living with persistent pain. By focusing on small, meaningful steps and consistent routines, individuals can regain a sense of control, improve mood, and expand their daily activities. Change is often gradual, but over time, behavioural activation can make a significant difference in quality of life and functional capacity.

References

Donaldson, L., Lamont, E., & McMillan, D. (2022). Behavioural activation for chronic pain: A systematic review and meta-analysis. Pain Medicine, 23(3), 542–553.

Ellingson, L. D., Stegner, A. J., & Cook, D. B. (2012). Physical activity and chronic pain: Mechanisms and interventions. Current Pain and Headache Reports, 16(2), 189–198.

Kamper, S. J., Apeldoorn, A. T., Chiarotto, A., Smeets, R. J., Ostelo, R. W., Guzman, J., & van Tulder, M. W. (2015). Multidisciplinary biopsychosocial rehabilitation for chronic low back pain. Cochrane Database of Systematic Reviews, 2015(9), CD000963.

Lee, H., Hübscher, M., Moseley, G. L., Kamper, S. J., Traeger, A. C., Mansell, G., & McAuley, J. H. (2021). How does pain lead to disability? A systematic review and meta-analysis of the role of avoidance. Pain, 162(10), 2479–2486.

Nicholas, M. K., Costa, L. d. C. M., & Hancock, M. J. (2023). Managing chronic pain: A clinical update. BMJ, 381, e073496.

Joon completed his Clinical Psychology training in New Zealand and has wide-ranging experience working in health, forensic and community settings across a number of different population groups. This has involved clinical roles in assessment and therapy, both as a lead clinician and as part of a wider multi-disciplinary team.